I worked as a volunteer physiotherapist at a refugee camp for a short time in 2016. The camp was in Greece and provided refuge to people escaping the war in Syria. It was an extraordinary time for me, I saw huge human suffering but also great courage and perseverance in the remarkable people I met.

So many of the people I met were experiencing very high levels pain, disability and drug-dependency – and I knew some of this was avoidable if only they had access to rehabilitation services. This wasn’t something I had expected. Prior to volunteering I had thought that physiotherapy would be a secondary consideration in a humanitarian crisis. Nice to have perhaps, but certainly not a priority. To my surprise I saw the potential for physiotherapists to make a stronger contribution than I had thought possible.

The following is the story about my time in the camp and of the people who live there. Please be aware before reading this that the people I treated had very painful stories regarding how they came to be injured. In the interest of providing a complete and accurate picture of life in a refugee camp I have not left those details out. I have also changed a few names and details in interest of providing anonymity to my patients.

I worked in a camp on Lesvos, an island much closer to Turkey than it is to the Greek mainland. The proximity of Lesvos to the Turkish coast makes it an attractive destination for refugees attempting to escape into Europe. Over one million refugees have landed on this small island since 2015. This map shows the journey my patients took to get to Lesvos from Syria. The trip can take weeks or months during which time people either walk enormous distances with whatever they are able to carry, or are packed by people-smugglers into overcrowded trucks and boats. Traveling like this was a cause of injury for many of my patients who suffered debilitating lower back and repetitive strain injuries along the way.

Many people suffered further injury in encounters with the Turkish police, at the hands of prison-guards, or while escaping capture at the Syria-Turkey border wall. These injuries included dislocations, ligament tears, cartilage damage and fractures. Others carried injuries with them which they had sustained during bombings of their home-towns and at the hands of ISIS.

Those who made it to Lesvos were received by Lighthouse Relief, an NGO established specifically to look after refugees as they arrived. Lighthouse Relief provides search and rescue services, first aid, clean clothes, and a place to rest. Most people did not stay at the Lighthouse Relief camp for long, usually leaving within hours to walk on to the main town of Mytilene in search of a boat to the Greek mainland.

I had initially organised to work with Lighthouse Relief managing acute injuries and providing walking aids for the long walk to Mytilene. However, just before I arrived on Lesvos the borders within Europe were closed and the number of new arrivals dwindled. Lesvos was now dealing with thousands of trapped people living in camps scattered around the small island. In order to see any patients, I needed access to the camps.

The camps all had varying levels of security but in general you needed to be officially working with an NGO in order to gain access. Even then it could be difficult, the most infamous camp on Lesvos (Moria) was essentially a prison complete with barbed-wire, armed security, and large cages separating single men and unaccompanied teenagers from women and families. In the end I gained access to Kara Tepe camp through a woman who volunteered distributing clothing. I spoke with the head doctor in charge of a medical clinic for a large international NGO, and he agreed to let me work alongside the doctors.

The clinic consisted of five paid doctors and two volunteer translators. However, the vast majority of patients seeking treatment at the clinic did not have medical conditions or infections, instead they had either musculoskeletal injuries sustained during their escape, or pre-existing injuries and disabilities caused by the war they were escaping.

On my first day at the clinic I treated a man with a rotator cuff injury he sustained jumping out of a two-story window to escape Turkish police, he kept his arm in a sling and was unable to lift it more than a few centimeters out from his side. I saw a woman who had had a shard of metal shoot through her back during a bombing back in Syria. The metal had been removed but she had ongoing muscle spasm and sciatic pain and was crawling around the camp or being pushed in a wheelbarrow. I saw a three-year-old with extensive scarring following burns sustained during a bombing in her hometown. The scars were not stretching as she grew and one hand and foot were gradually curling inward and becoming unusable. I saw a six-year-old with cerebral palsy who had arrived without his walking aids and was unable to walk or sit up without assistance.

Doctors are great at the pharmaceutical and surgical sides of patient treatment. However, they are not trained in the rehabilitation of burns-related scarring or cerebral palsy, and without any x-ray or MRI machines they lack the skill-set to diagnose musculoskeletal injuries or to treat them. The only treatment the camp-doctors were able to offer inured patients was pain management in the form of medication. This resulted in a mini opiate-crisis within the camp including early signs of addiction and the stockpiling of opiates by refugees who wanted to commit suicide.

My very first patient at the clinic was Amira, a woman from Damascus who had been a languages teacher. Because her English was so good I got to know her the best of anyone else I treated. Her husband had been kidnapped by ISIS, she didn’t know if he was still alive, and one of her brothers was found murdered. She had a brother in Germany she was hoping to stay with but had left her mother, sister, and a niece behind in Damascus. She had low back and neck pain following a series of beatings she had suffered before escaping Syria. She was unable to sleep for more than an hour or two at a time or to stand for longer than ten minutes.

The doctors had been unable to diagnose Amira’s injuries and offered treatment in the form anti-inflammatory medication. She had refused the opiates. It had been several months since she had sustained her injuries and she had healed from the initial damage. Her ongoing pain was caused by muscle tension and scarring at her low back and gluteal muscles, a loss of core and hip control, and a muscle imbalance she had developed as a result of limping. Deep tissue muscle release, strengthening, and gait retraining began to ease her symptoms, and she was able to sleep through the night by the time I left the camp.

On my second day I visited the tent of a woman called Farah who was in too much pain to get to the medical centre. She had low back pain with severe spasming, possibly just as a result of sleeping on the cold ground every night. She had arrived with her four small children who roamed the camp unsupervised and was severely depressed. Trapped on a small Greek island unable to move let alone look after her kids she wondered why she had bothered to escape Syria in the first place. She had used opiates to attempt suicide the previous week. I don’t know if she received any life-saving treatment at any point during her to journey to Lesvos, but it occurred to me that the treatment was pointless if she could not see a reason to continue to live and took her own life in the end.

I couldn’t get her to move enough to properly diagnose her but I had some fundraising money left over and used it to buy some instant heat-packs in Mytilene. She used these at night as a way to ease the spasm and help her get some sleep. She was grateful for the help and did start to sleep better, the spasm eased enough for her tolerate deep-tissue massage at her lower back muscles and to start doing some light stretches. However, I left camp before I could get to the bottom of her problems and I don’t know how things went for her in the end.

These cases and others like them were enormous eye-openers regarding the vital importance of rehabilitation services in settings like this. By the end of my time on the island I was pretty sure that if there had been one or two full-time physios in the camp there may have been a need for only one or two doctors, and many patients would have seen better outcomes. Doctors are of course essential in the treatment of medical conditions, however musculoskeletal injury is not their area of expertise. Physiotherapists are much better placed to deal with injury and disability and we need more of them in settings like this one.

I left Greece wondering why there weren’t more physiotherapists working in humanitarian settings. I did some googling and found that there are in fact a handful of NGOs who hire physiotherapists to work in war-torn and under-resourced areas, following natural disasters, and in refugee camps. However, the visibility of this work is low as the media often assumes that medical staff in humanitarian settings are all either doctors or nurses.

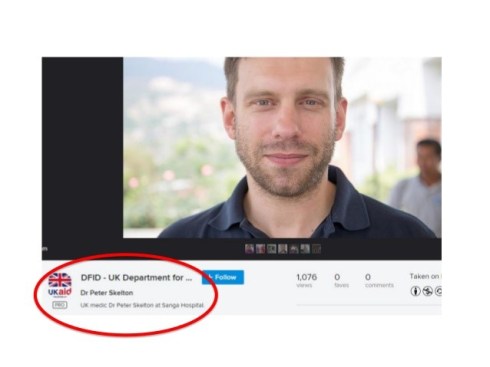

The under-representation of rehabilitation professionals in the media is illustrated in the photo below. This man is Peter Skelton, a physiotherapist who works for a French NGO called Handicap International which specifically focuses on rehabilitation. However, here he is in a news report incorrectly identified as a doctor. Pete was involved in bringing the importance of rehabilitation to the attention of the World Health Organisation who have recently adjusted their guidelines to require all surgical teams attending a crisis to also provide post-operative rehabilitation services – a sign that things might be starting to move in the right direction.